|

the rest: journal of politics and development |

||

| RESEARCH ARTICLE the rest | volume 10 | number 2 | summer 2020 | ||

| Chuks. I. Ede* and Nokukhanya Noqiniselo Jili**

* Department of Public Administration, University of Zululand: 60026774@mylife.unisa.ac.za ** Department of Public Administration at University of Zululand, JiliN@unizulu.ac.za |

||

| ARTICLE INFO | ABSTRACT | |

| Keywords:

Service delivery; Protests; South Africa; Megalopolises, Government

Received 26 March 2020 Accepted 16 June 2020 |

One of the bequests of the current democratic dispensation in South Africa is the choice by the citizenry to express their feelings without let or hindrance. Since 1994, the people of South Africa have recouped much power as to expressing their grievances towards their government in some of the worst viciously known manners ever recorded among black Africans within the continent–. Since recent times, South Africans have aggravated their protest revolts over what they perceive as government’s failure in the delivery of vital (basic) services, such as electricity, water and sanitation, with some other protests flanking on the provision of quality higher education at affordable cost or possibly no cost at all. With incidents of violent protests almost becoming frequent occurrences, the main aim of this article is to explore the main question that is still remaining “Do South African mega cities really stand to lose much more for not doing enough for their constituencies”? Attempts at providing answers to this question have resulted in an in-depth reviewing of literature into the antecedents of service delivery protests in South Africa. The article reveals that the cost of unaccountability by the failure of megalopolises’ authorities to render adequate municipal services to their people, outweighs by far the very cost of remedying the situational consequences accruing therefrom. Therefore, South African cosmopolitan authorities must be able to deliver based on the expectations of their masses who elect them into power; they also need to put adequate security measures in forceful place to clampdown on civilian protestors in their megalopolises. | |

Introduction

Since the dawn of democracy in 1994, most especially after the iconic presidency of South Africa’s democratic founding father, late Nelson Mandela, South Africans have always fathomed reasons to strike back at their government over what they perceive as its failing or insufficient capacity to deliver basic services to the people. Hardly would a full calendar year elapse without any incident of such mass revolt by the people against government at all levels, and the majority of these protests are as destructive as they are mostly understandable or unwarranted. The culture of “service delivery protests” in South Africa has, therefore, graduated to an orthodox level where most disgruntled elements in the society are more disposed to reproaching government at any slightest exasperation in order to find defaulting basis so as to incite their fellows and other members of their communities against it. According to Jili (2012: 1), this “phenomenon of violent confrontation against” [government over alleged] poor service delivery has become [so] problematic over the past several years”, that the nation’s Institute for Security Studies now reports it as “one of the highest rates of public protest in the world”.

Notwithstanding the alarming state of these protests with the scale of damages arising therefrom, majority of South Africans vividly express little or no compunction with regards to their involvement in past protests, thereby raising fears over the tendencies for more violent demonstrations in near or far future. This fear is also expressed by Peter (2010) while observing that more South Africans have, “since 2004 … experienced a movement of local protests amounting to a rebellion of the poor”. With the protests becoming “widespread and intense, [and] in some cases reaching insurrectionary proportions” (Jili 2012: 29), Roelofse (2017: 2) attributes “poverty, poor performing municipalities, lack of state resources and more often, mismanaged funds [which] create budgetary constraints to fulfil elections promises”, as their root causes. The above studies have shown that these service delivery protests affect the country and the people in more than fewer ways. Roelofse (2017: 1) continues to reveal that service delivery protests “have impacted South Africa in a [rather] significant way”, leading to some worst-case scenarios where innocent lives went therewith. He opines that one of such incidents was so gory that the state television broadcasting corporation, SABC, issued a “policy statement that violent protests will not be screened” on national TV thenceforth (Roelofse 2017: 1). This has aroused so much concern over the increasing level of frustration-induced aggressions by the people towards their government.

The aim of this paper, therefore, is to analyse in details what South African megalopolises or (mega cities) stand to lose from wanton protests even as they are failing or faltering to deliver (much) for their constituencies. To achieve this, attempts are made in providing an adequate theoretical premise for service delivery protests, based on the precept that they are caused by municipal non-/underperformance. This might, perhaps, divulge more reasons as per why South Africans are most likely to end up in violent protests, the majority of which are regrettably deadly. Additionally, efforts are made in analysing the situational reports of service delivery protests in these megalopolises most affected across various provinces in the country, with particular reference to those mega cities which are considered as “hotspots” for service delivery protests. This article eventually reports the possible impact of these protests on the various municipal economies.

Conceptual Clarification of Service Delivery Protests

There are as many definitions as there are many cases of service delivery protests in South Africa, but the premise of popular definitions entails that service delivery protests are

communal demonstrations borne on agitations over inadequate or inexistent municipal services, development indices or governmental accountability.

An attempt to render separate conceptualisation of the composite words might perhaps enhance proper understanding of the subject matter in this article. According to Samkange, Masola, Kutela, Mahabir, and Dikgang (2018: 1), “protests are defined as social movements in which people with a common purpose respond to policies set out by authorities”. According to Van Vuuren’s (2013: 15) reportage which alludes to University of the Western Cape’s definition of the concept, ‘social protest’ embroils “any complaint or issue cited by protesters, whether related to service delivery claims or not, over which citizens decide to engage in protest activity”. While Van Vuuren’s definition emphasises the subject of these protests, instances abound where public attention can be drawn to the object or incident of these protests, or what they usually result into. This is probably the situation which Lancaster describes as proportional to a state of unrest (Lancaster 2018: 29a).

Deducing from the above; therefore, Matebesi and Botes (2017), Morudu (2017) as well as Jili (2012) render perspective accounts on what ‘service delivery protests’ are all about. Starting with Jili who defines the concept exclusively, ‘protest’ is “a formal objection, especially by a group … [or] a collective gesture of disapproval, sometimes violent, to make a strong objection or to affirm something”; while ‘service delivery’ represents those things which “the municipality are (sic) responsible for ensuring that people in their areas have at least basic services they need … in particular water, electricity, sanitation, houses and roads” (Jili 2012: 11). Concurring with Jili, Reddy (2016: 2) interjects that ‘service delivery’ is the “provision of municipal goods, benefits, activities and satisfactions that are deemed public, to enhance the quality of lives in local jurisdiction”, while Morudu (2017: 3) recapitulates ‘service delivery protests’ as arising “due to changes in a number of service delivery indicators”. But a more detailed explication of the concept is offered by Matebesi and Botes (2017: 82). According to them,

“Service delivery protests … mean collective action by a group of community members against a local municipality because of poor or inadequate provision of basic services, as well as a wider spectrum of concerns including government corruption, rampant crime and unemployment”.

One of Alexandra’s (2010: 25) classifications of service delivery protests is buttressed by Lancaster (2018: 29). In her opinion, “a society’s preference for the use of conventional forms of political participation … can, over time, transform into unconventional political participation like violent protest or political violence” (Lancaster 2018: 29), which is simply the case with most service delivery protests in South Africa. Consequently, it is neither easy to estimate the condition that makes the choice for each ‘political participation’ in a community, nor the appropriate period when the use of such approach is legitimate and therefore obtainable. This is, perhaps the reason Lancaster (2018: 29b) argues that the basis for a community’s or society’s choice of protest – whether peaceful or violent (conventional or nonconventional) – as well as the justification for the use of any protest action whatsoever in the first place, absolutely depend “not only … on the period of time in which it takes place, but also on the geographical location, and that particular society’s definition of what is socially acceptable”, or not. By context, this provides some insight on the legal basis of protests within a state, as well as what these protestors might claim as the premise for their protest actions.

To this effect, this article argues that there is quite as much conjectural premise to substantiate service delivery protests in any society whose administrative system is adjudged to be nonperforming, inasmuch as there is hardly – regrettably – any substantive basis for the seemingly ‘unreasonable’ spate of protest-related destructions in South Africa, many times some civilian lives are lost thereby. So, are South Africans actually becoming too assertive by taking their protest actions to extreme heights? Before delving through some provincial situational analysis to get answers to the level of losses attributable to service delivery protests in the country’s main cities, it is important to analyse the theoretic premise of these protests.

Theoretical Premise of Service Delivery Protests

With sincere regard to the height of destructive tendencies of service delivery protests in South Africa, it is not unlikely that these ‘protests’ are an indispensable practice in any democratic setting. But in as much as there is no justification for the majority of these extreme forms of service delivery protests in the country, there is in fact some Constitutional provisions for service delivery in South Africa. Section 152 of the Constitution of the Republic of South African (1996) provides the right to service delivery for all South Africans, as it also specifies that various governmental institutions at municipal or local government level be vested with such power to delivering equitable services to the people at a grassroots level. Writing on behalf of Afro barometer, a “pan-African … research network that conducts public attitude surveys on democracy, governance, economic conditions and related issues in Africa”, Sibusiso Nkomo specifies that the above Section of the South African Constitution charges the “Local government [to] … among other things, with ensuring the provision of services to communities in a sustainable manner, promoting social and economic development, and promoting a safe and healthy environment” (Nkomo 2017: 2). Alluding further to the South African Organised Local Government Act of 1997, Nkomo captures the structural composition of the three types of Municipalities which wield such Constitutional power as local governmental institutions in the country, including “eight Metropolitan cities [or megalopolises], 44 district municipalities, and 226 local municipalities” (South African Government 1997, in Nkomo 2017: 2). “All these types of municipalities”, according to him, “have a core responsibility for water, sanitation, markets, refuse removal, and land management” (Nkomo 2017: 2).

However, inasmuch as South Africa’s Constitution acknowledges the people’s right to service delivery in their communities, there is so much concern as per the level of exacerbated and destructive protests, many of which clearly leave the cities in much worse condition than they were even with the alleged inadequate or inexistent municipal services. However, Roelofse (2017: 6), aptly objects that Cape Town does somehow ‘recognise’ these service delivery protests as one major expressive way which the masses employ, apparently at breaking points, when it appears their ‘patience’ is running out. According to him, “the Parliament of the Republic of South Africa (2009: vi) notes that violent service delivery protest is caused by aggression that is fuelled by frustration” over the prolonged failure of these municipalities to respond to people’s cries and meet their needs (Roelofse 2017: 6). While considering the extreme level of wanton destruction which always results from most of the protest actions, we are still unable to confirm if the same National Parliament could justify their means as ultimate and fairly responsible, in a situation where these protestors claim their needs are inadequately met (or not met at all). This is much like a quagmire wherein two wrongs are austerely contending to make a right. And whereas Salgado (2013: 17) argues mainly in favour of the protestors where, he says, always suffer “long standing alienation by large sections of [their] community”, Roelofse (2017: 6) decries incessant marginalisation of the local communities generally by their local government as the principal reason why they go extreme:

“When such marginalisation becomes the norm, and communities are robbed of active citizenship, the resulting levels of frustration may lead to the notion that the only way to make their voices heard is through the use of headline-grabbing violence”

Surprisingly, Lancaster (2018: 29b-30a) harangues that more and more South Africans appear to be participating in violent protests as a leeway to registering their grievances over what they perceive as anomalous in the social system, and they believe that it is working for them. She infers on Bohler-Muller’s et al (2017) study which states that:

“Disruptive and even violent protest may be becoming more acceptable, given that a growing number of South Africans believe these forms of protest yield more successful results than peaceful protest action.”

Jili (2012: 66), on the other hand, registers on the futility of any hope that these protestors are relenting any time sooner, because the majority of the South Africans are still in doubt of their government’s capacity and efficiency in delivering adequate municipal services to them (see Figure 1 below).

Perhaps, a more logical proposition of why protests do occur, and how frustration does ‘fuel’ such protest actions, is likely deducible from the field of Psychology, where human behaviour is studied. Social and behavioural scientists have, therefore, made crucial attempts in order to demystify this extant notion that frustration does actually lead to aggression, and the cause of this frustration, as well as the degree and trajectory of the consequent aggression, can be measured and most probably projected. Jili (2012: 4) suggests that the best hypothetical justification for violent service delivery protests in South Africa, is John Dollard’s “frustration-aggression theory”. The theory, which originates from Dollard in 1939, is described by Barker et al (1941) as “a psychological factor underlying violence, [wherein] aggression [is] caused by frustration resulting (sic) from unfulfilled expectations” (see Jili 2012: 4). Alluding to Dollard et al (1939), Friedman et al (2014) state that aggression is the result of blocking, or frustrating a person’s effort to attain a goal. Therefore, by its earliest formulation, the frustration-aggression theory states that frustration always precedes aggression, and aggression is the sure consequence of frustration (Dollard et al 1939). With cognitive regard to the South African scenario of service delivery protests, the underlying problem always manifests therefrom when “this frustration turns into aggression [as] something triggers it, for instance, a realisation by citizens that they have waited too long for the services to be delivered [or] promises of service delivery made by government are broken and the politicians, from the perspective of the people, are elitist” (Jili 2012: 4). Nonetheless any apparent concern for the kind of violent demonstrations as currently witnessed in South Africa with such inestimable and – most times – irreplaceable loses on both sides (government and the governed alike), and with no specious deference for whose ox was gored first, or what causes what which then vindicates what outcome, this study’s nonaligned objection remains unequivocal over the untold socioeconomic quagmire which the government and people of South Africa are steadily grounding the country with its economy. The current situation has become so critical that it does actually appear that for every one major development step they take for the country to move forward; two or more retrogressive steps are incurred as a result of such vicious protests over poor service delivery in the country. Thankfully, the scholarly contributions of Hovland and Sears (1940), Barker et al (1941), Harris (1974), and Kulick & Brown (1979), are highly esteemed in providing the much-needed insight as well as necessary (re)examination of Dollard’s et al (1939) ‘frustration-aggression theory’, as the justice of applying it to South African context is the prerogative of this article.

The interventionist contributions of Harris (1974) and Kulick & Brown (1979), attempt to further illustrate this extent unto which frustration could conceivably mature to aggression. Their “Refinements” efforts measure the degree at which frustration could ultimately determine both the prospect of aggression and the implications thereby. They, therefore, demonstrate that the greater the degree of frustration, the greater the likelihood of aggression which emanates therefrom. Put in simplest form, frustration is increased by being thwarted, when a need is left ‘over-duly’ dissatisfied or an expectation is insolently (unapologetically) violated or disappointed. The higher the amount of those expectations or the period over which the needs are left unmet, the tendency is they are most probably going to result in a state of diffusion, which occurs after a boiling point upon which the endurance thread of the individual or group is regrettably broken. This is a point of no return where the accrued aggression keeps diffusing spontaneously and randomly on impact at any available object or receptor; conventionally on the exact source or cause of the frustration when the aggression is directly projected, or unconventionally on a nearby object or ‘scapegoat’ when it is indirectly projected.

These theoretical expositions rightly unravel the situation of service delivery protests in South Africa, but they do not in any way justify the extreme or unconventional forms of most protest actions in the country. They do, as a matter of principle, illuminate that these protests have a basis or causative stimuli, which are quantifiable. And if ardent care is taken by means of tracking and cushioning their basis or the causes of frustration, the deplorable outcome that would have led to the state of boiling point when the frustration is readiest for diffusion, could have been barred, with normalcy retrogressively restored effectively. This is important and practicable considering the spate of wanton criminality and destructions arising from service delivery protests in South Africa. Morudu (2017: 3) testifies to the “proliferation of [these] service delivery protests in South African local municipalities, as regularly seen in the media”. Public Servants Association (2015: 8), on the other hand, is still surprised that “service delivery protests are most common in major metropolitan centre like Johannesburg, Ekurhuleni and Cape Town”; while Jili (2012: 8) proclaims that since recent times, “South Africa has experienced a wave of violent protest action across most provinces”. Therefore, at whatever level where these protests occur, their situational report is always too gory to behold. For the purpose of this article, the situation of these destructive protests across major provincial megapolises in South Africa will be taken into consideration.

Provincial Situational Analysis on Service Delivery Protests

Section 40 (1) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (Act 108 of 1996) recognises government at national, provincial and local spheres, as “distinctive, interdependent and interrelated”. To this effect, there is one national government whose executive, legislative and judicial arms are stretched across countrywide in Pretoria, Cape Town and Bloemfontein respectively, nine provinces with their capital cities, and over 278 municipalities at local government level where most of the service delivery protests do occur, based on the reality that every part of the country is enumerated under one local municipality government.

Citing Bhardwaj (2017), Roelofse (2017: 9) observes that South Africa has witnessed 10 517 service delivery protests from 2012-2013, 11 668 service delivery protests from 2013-2014, and 12 451 service delivery protests from 2014-2015. Within these triple-phased periods, “there was thus an increase of 1 934 incidents or 18,39% (sic) over the three years” (Roelofse 2017: 9). Although “there is also a gradual increase in the [number of] peaceful [protest] incidents” (Roelofse 2017: 9), Bhardwaj (2017) argues that there were 1 882, 1 907 and 2 289 unrest-related incidents respectively within those periods “which reflect an increase of 407 or 21,6% (sic)” in all violent protests in the country (see Roelofse (2017: 9). He, therefore, projects an “upward trend in protests” as the majority of “the 278 municipality in South Africa grapple with limited budgets and increasing demand for houses, water, electricity, and other services”, resulting in inadequate or inexistent service delivery to the masses as “it [currently] affects 5 of the 9 provinces, namely Northwest, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, KZN and Eastern Cape provinces” (Roelofse 2017: 9).

According to Roelofse (2017: 10), South African local “municipalities … are [further] classified into Metros, District Municipalities and Local Municipalities”. Local municipalities are further categorised into four (4), including B1, B2, B3 and B4, in accordance with the Municipal Infrastructural Investment Framework (MIIF). The above categorisation means that B1 is made up of secondary cities and local municipalities with the largest budget; while B2 includes any local municipality with a large town at its core. B3, on the other hand, comprises of local municipalities with no large town at its core, but small towns with a relatively small population many of whom live in small urban areas; whereas B4 category is almost entirely rural with communal tenure and one or two small towns in their area (Municipal Demarcation Board 2012, in Roelofse (2017: 10). According to Roelofse (2017: 10), the Western Cape province, Free State province and Gauteng province do not have any B4 local municipality, whereas in the remainder of the provinces, the distribution of the B4 “poverty horseshoe” municipalities are as follows: Northwest – 2, Limpopo – 16, Mpumalanga – 5, KZN – 29, and Eastern Cape – 15. This analogy most accurately underpins the high incidents of service delivery protests in the abovementioned hotspots, but that does not mean that such protests have not or cannot take place in other provinces in the country.

Impact of Service Delivery Protests on Municipalities

The “status of service delivery” among municipalities, according to Roelofse (2017: 9-10), is somewhat steadily awful with most underdeveloped areas at local government level facing “the inability … to raise income, be it through taxes, delivery of services and other modes, such as business levies and access to amenities”. And since “poor municipalities” generally translates to poorer populace within those municipalities, their tendency to wholly rely on the national government for their funding needs, becomes almost unavoidable (Roelofse 2017: 9). Their rampant state of poverty, with gradually failing service delivery capacity, has resulted in more chances of protests being recorded within those municipalities this article, therefore, acknowledges some typical cases of service delivery protests in selected municipalities. According to Bohler-Muller et al (2017: 82b), the bulk of South Africa’s protests actions emanate from “economically disadvantaged” members of the society who grapple with challenges relating to “municipal services and other material issues” including “poor state of wages and labour market opportunities.” Samkange et al (2018: 5-6) illustrate that the city of Johannesburg accounts for most of the protests in overall, with “approximately 41% of all protests during 2010-2017 period …, [with] 23% in the city of Cape Town and 19% in the city of Tshwane” (See Figure 1). “This means that 60% of all protests occurred in the Gauteng province [as] Manguang metropolitan has the lowest percentage with 0.0047%~0% of all protests during the period under review” (Samkange et al 2018: 6).

Samkange et al (2018: 4) observe that the above municipalities were most affected in the areas of “impairment of plant, property and equipment as well as impairment of movable assets … used as a proxy for protest-related” exercises, for which huge sums were budgeted to offset their loss or damage. Samkange’s et al’s (2018: 5) further report of service delivery protests in South African metropolitan municipalities reveals that these protests take the forms of both violent and non-violent. Whereas non-violent protests involve peaceful demonstrations during which the protestors array no or fairly agitated movements with placard displays to express their grievances, the violent protests, on the other hand, incur tense or agitated movements with more or less destructive tendencies.

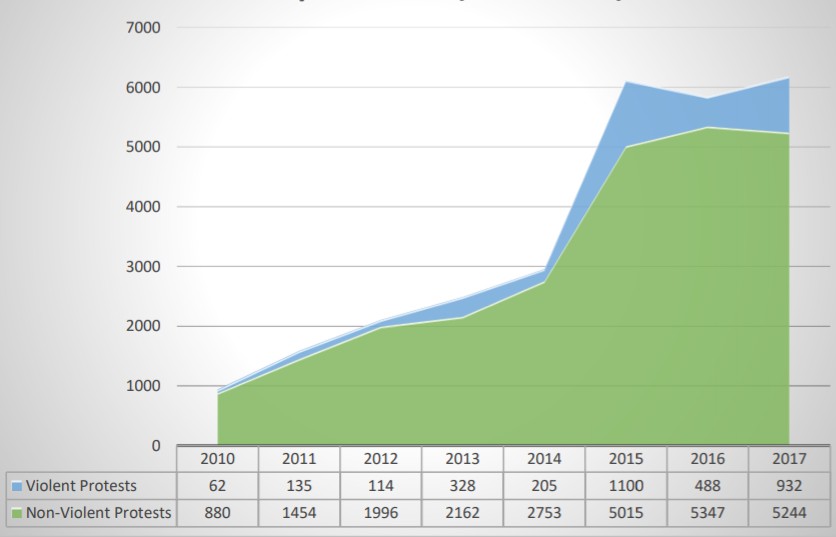

Figure 1: Total protests in South African metropolitan (mega cities) municipalities (2010-2017)

Source: Samkange et al (2018: 5).

In their special investigation for the Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC), Nomdo and Siswana (2020) report that this kind of violent protests occurred in Mandeni, a traditional manufacturing hub on the north coast of KZN, in 2016. According to their report,

“The town was rocked by [violent political] protests related to the election of a ward councillor and the inability of the local authorities to heed the community’s demand. The protests [then] turned violent which led to the burning down of factories in the region, leaving more than 2 000 people out of work. As a result of the destructive protest, local residents lost sources of income and capital needed to send their children to school, access services and purchase food, which led to monetary deprivation”.

Figure 2: Violent Protests and Non-Violent protests in South African mega cities (2010-2017)

Source: Samkange et al (2018: 8).

According to Samkange et al (2018: 7-8), the above graphical representation of the evolution of service delivery protests in South African major metropolitan cities shows that the number of both violent and non-violent have also increased substantially from 942 in the year 2010, to 2 490 in 2013, with a drastic upward trend to 6 176 in the year 2017. “This shows an increase display of dissatisfaction by the South African public” (Samkange et al 2018: 8). In the same vein, the figure reveals that violent protests gained significant momentum from 62 in the year 2010 to 932 towards the end of the period under review, which translates into a staggering fifteen-fold magnitude increase of what it was in the year 2010 (see Samkange et al 2018: 8). By this analogy, evidence abounds to the certainty of intensifying incidents of service delivery protests in general, and more violent service delivery protests in particular. It further goes to state that there is no gainsaying the fact that the people of South Africa are not relenting in their choice ways by which they express their grievances towards their government. In another study conducted in 2011 on people who stay in the informal settlements of Khayelitsha, a partially-informal township in Western Cape, Nleya finds that 54% of the people (residing in informal settlements) confirm that they “would attend protests regularly [while] 36% of the people residing in formal houses say they would be involved in public protests regularly”. More studies which were conducted in the same year, such as the study by Karamoko & Jain (2011), “found that 56.64% of protests that took place throughout the country were violent in 2010”.

Conclusion

If the municipal authorities in South African megalopolises presume they can always smartly win their masses’ support during their electioneering campaigns and subsequent votes during elections, like a miserly satyr who is counting on his wonted bedtime promises just to win yet another night’s pleasure from his credulous spouse, then we assume in this article that they have bargained more than they could afford and are definitely in to count more losses. This is because the masses are now increasingly angered by frustration of inadequate cum inexistent service delivery within their megalopolises, and it is obvious that there are no worse ways they express it than through violent protests. After diligently perusing a popular survey which links “service delivery and protests in South Africa” and wherein we still hear that a whopping 54% of people who stay in informal settlements are warming up to “attend protests regularly” with as much as 36% of their counterparts in formal houses also signalling they are ready to “attend public protests regularly”, we were almost frustrated by the sickening and unreasonable level of wanton destructions akin to these violent protests in the nation’s megalopolises (but our own frustration won’t lead to any aggression). That is why this article concludes that the gory pictures from these protest-induced destructions should better be kept in people’s mind than explicitly represented in this article.

From the foregoing, it is crystal-clear that the cost of unaccountability by the failure of megalopolises’ authorities to render adequate municipal services to their people, outweighs by far the very cost of remedying the situational consequences accruing therefrom. There is, therefore, no gainsaying the fact that the options before South African cosmopolitan authorities are twofold: either by leading up to the expectations of their masses who elect them to power or by putting adequate security measures in forceful place to clampdown on civilian protestors in their megalopolises. As it stands now in South Africa, the former option appears feasible and might be the painstaking choice for megalopolises whose political and administrative officeholders are notorious for corruption and unaccountability to their people. This is imperative since the consequences of the latter – which can result in enormous carnage – might be far worse costly for a continental leader like South Africa to subscribe, whose decades-old democracy is epitomic in Africa. To act otherwise, is to expect just too worse.

References

Alexander P (2010), Rebellion of the poor: South Africa’s service delivery protests, A preliminary analysis. Review of African Political Economy, 37 (123): 25-40.

Barker R, Tamara D and Kurt L (1941), Frustration and regression: An experiment with young children. Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa Studies, Child Welfare.

Bhorat H and Kimani M (2018), South Africa’s growth trap: The constraints on economic growth and the role of water. Water Resources Commission, 2601/1/18: 1-23.

Bohler-Muller N, Roberts BJ, Struwig J, Gordon SL, Radebe T and Alexander P (2017), Attitudes towards different forms of protests in contemporary South Africa. SA Crime Quarterly: 62: 81-92.

Clark JP (1991), The Wives’ Revolt. Ibadan: University Press.

Dollard J, Miller N, Doob L, Orval H, Sears R (1939), Frustration and Aggression. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Friedman H and Schustack M (2014), Personality classic theories and modern research. (5th Edition). Boston: Pearson: 204-207.

Jili NN (2012), The perceptions on youth on service delivery violence in Mpumalanga province. Master’s dissertation: Department of Public Administration, University of Zululand.

Karamoko J and Jain H (2011), Community protests in South Africa: Trends, analysis and explanations. Community Law Centre: University of the Western Cape.

Kulick JA and Brown R (1979), Frustration, attribution of blame and aggression. Journal of Experimental and Social Psychology, 15: 183-194.

Lancaster L (2018), Unpacking discontent. South African Crime Quarterly, 64: 29-43.

Mahlatji M and Ntsala M (2016), Service delivery protests resulting in the burning of libraries. SAAPAM Limpopo Chapter conference, Chapter 5th Annual Proceedings: 219-227.

Matebesi S and Botes L (2017), Party identification and service delivery in the Eastern Cape and Northern Cape, South Africa. African Sociological Review, 21(2): 81-99.

Miller N (1941), The frustration-aggression hypothesis. Psychological Review. 48 (4): 337-342.

Morudu HD (2017), Service delivery protests in South African municipalities: An exploration using principal component regression and 2013 data. Cogent Social Sciences, 3 (1329106): 1-15.

National Treasury (2018), Municipal audited financial statements (2010-2017). National Treasury Department: Pretoria.

Nkomo S (2017), Public service delivery in South Africa: Councillors and citizens’ critical links in overcoming persistent inequalities. Afrobarometer Policy Paper, 42: 1-16.

Nleya N (2011), Linking service delivery and protests in South Africa: An exploration of evidence from Khayelitsha. Africanus, 41(1): 3-13.

Public Servants Association (2015), The challenges of service delivery in South Africa: A public servants’ association perspective. Pretoria.

Reddy PS (2016), The politics of service delivery in South Africa: The local government sphere in context. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in South Africa, 1817 (4434): 1-8.

Roelofse CJ (2017), Service delivery protests and Police actions in South Africa: What are the real issues? Journal of Public Administration and Development Alternatives, 2(2): 1-22.

Samkange C, Masola K, Kutela D, Mahabir J and Dikgang J (2018), Counting the cost of community protests on public infrastructure. Pretoria: South African Local Government Association.

Van Vuuren L (2013), Poor and angry – Research grapples with reasons behind social protests. The Water Wheel Seminar of November-December 2013: 14-16.