| the rest: journal of politics and development | ||

| RESEARCH ARTICLE the rest | volume 10 | number 2 | summer 2020 | ||

| Mfundo Mandla Masuku*, Primrose Thandekile Sabela** and Nokukhanya Noqiniselo Jili***

* School of Development Studies at the University of Mpumalanga, Mandla.Masuku@ump.ac.za ** School of Commerce and Management, at the University of Mpumalanga, Thandeka.Sabela@ump.ac.za *** Department of Public Administration at the University of Zululand, JiliN@unizulu.ac.za |

||

| ARTICLE INFO | ABSTRACT | |

| Keywords:

Development; Government; National Health Insurance; South Africa; Tax

Received 27 March 2020 Accepted 15 May 2020 |

This paper aims to provide a critical review of the proposed National Health Insurance Bill in South Africa with reference to the finance mechanisms and implications within the development context. This starts with a brief analysis of health coverage, looking at the international and local context and describes the development benefits of the NHI. The paper reviews the funding mechanisms with particular reference to the tax incidence of the different types of taxes that could be used to raise funds for the NHI. Fiscal policy implications of the proposed health care provision changes are also discussed, and the proposed NHI Fund evaluated, focusing on the impact on the achievement of a performance-based budgeting system. The paper concludes that the increase of income and consumption-based taxes could result in loss of welfare to society, as labour is discouraged from working and the poor are further disadvantaged through increases in taxes such as value-added tax. |

|

Introduction

The National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill presents South Africa with an opportunity to restore the disequilibrium in access to healthcare services in the country. Basically, the NHI proposes to achieve sustainable and affordable universal access to quality healthcare services for all people living in South Africa. The proposed National Health Insurance programme is informed by the aims of the Universal Health Coverage (UHC) initiative, a global aspiration to provide quality health services to all irrespective of class, colour, age, gender and other attributes (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2018). South Africa as a signatory to the World Health Assembly’s resolution (67.23) of 2014 entitled ‘Health Intervention and Technology Assessment in Support of Universal Health Coverage’, pledged to deliver quality health to all through the National Health Insurance mechanism.

In principle, the NHI should be welfare-enhancing, as it is aimed at providing access to quality healthcare for all citizens regardless of their income level or status. The present system in South Africa fails to promote equal access to health services, as just over 16% of the population has health insurance and can easily access quality health services in the private sector (Mcleod et al., 2008; Harris et al., 2011; 25 Year Review Report, 2019). An estimated 21% of the population is actually not covered by health insurance but can afford to use private health services, while more than 63% are reliant on the public sector for their conventional healthcare services. The majority of the population has been relegated to the inefficient public sector healthcare system, which makes healthcare supply skewed in favour of individuals with high income. As elucidated in the NHI Bill and other studies (Harris et al., 2011; Mayosi and Benatar, 2014), there is a need for a comprehensive public health framework capable of delivering equitable universal healthcare. Private health insurance systems tend to exacerbate inequalities and provide coverage only for the wealthy or well-off.

However, the success of the NHI in delivering equitable healthcare depends on the success of the proposed healthcare revenue mobilisation programmes, the health procurement system, and the macroeconomic implications of such decisions. The available literature on the NHI has not paid adequate attention to methods that will be used to deal with public sector challenges such as financing mechanisms and implementation for the development and provision of quality healthcare. This paper, therefore, is aimed at providing a critical review of the proposed National Health Insurance Bill with reference to the finance mechanisms and implications within the development context. The paper starts with a brief analysis of health coverage, looking at the international and local context, and describes the development benefits of the NHI. The following parts review the funding mechanisms, with special reference to the tax incidence of the different types of taxes that could be used to raise funds for the NHI, discuss the fiscal policy implications of the proposed healthcare provision changes, and evaluate the proposed National Health Insurance Fund focusing on the implications for achievement of a performance-based budgeting system.

Health Coverage as an Issue in the South African Context

The universal health coverage enshrined in the United Nations Sustainable Developments Goals (Number 3) aims to ensure that everyone has access to high-quality healthcare services and that no one becomes impoverished because of ill health (WHO, 2018). Section 27 of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (1996) also emphasises that everyone has a right to access to healthcare services. Two aspects covered in universal health coverage include adequate healthcare coverage and population coverage (healthcare for all). Despite the declaration of health as a fundamental human right by the WHO and other institutions, it is reported that half of the world’s population is without full coverage of basic health services and countries devote only 10% of the general government expenditure to health (WHO, 2018). Further noted is the fact that about 12% of the world’s population spends 10% of their household budget on healthcare. World Health Organisation (2019) also reports numerous challenges faced by the population in low-income countries, including South Africa, such as having less access to basic health services for prevention and treatment, experiencing a shortage of health professionals, and the fact that government expenditure in these countries tends to be lower despite the greater health needs observed.

Concern over access to healthcare in South Africa cannot be treated as a new phenomenon. In 1944, during the colonial era, a scheme for a national health service similar to the British model and comprising free healthcare and other health related benefits was proposed, though it was never implemented. The apartheid era saw an increased orientation towards the free market and insurance-only principles for private health insurance (Mcleod, 2008). However, the period after 1994 saw major transformative changes in healthcare, guided by the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (1996), the 2002 Taylor Committee Report, and finally the newly formed comprehensive health plan in 2019 (which included a mandatory insurance system). Moreover, the South African Constitution, Section 27 (1) (a); (1) (c) and Section 27 (2), recognise the right of access to health by all, obliging the state to take reasonable legislative and other measures within available resources to ensure the progressive realisation of this right. Chapter 2 of the Constitution of South Africa, the Bill of Rights, encapsulates socio-economic rights that relate to housing, healthcare, food, water and social security. Outcome 2 of the National Development Plan, Vision 2030 makes provision for an integrated healthcare system aimed at serving the needs of all, free at the point of service, and paid for by publicly provided or privately funded insurance.

Considerable progress has been made during the democratic dispensation to reverse the discriminatory practices that prevented certain sectors of the population from gaining access to basic services. Health status has improved over the past 25 years because of key interventions aimed at strengthening the health system, and provision of other health related necessities such as clean water, housing and proper sanitation. The period before 1994 saw health issues being overshadowed by militaristic issues, yet health has gained pre-eminence as an issue of national security. Average life expectancy has increased to 65 years from 54 years, and the health of children, women and special groups has improved. The use of public sector health facilities also increased from 44, 7% to 71, 5% between 2004 and 2018. Household income has increased by 273,9% over the past 25 years (25 Year Review Report, 2019). The achievements and transformative arrangements noted are indicative of improved access to healthcare.

Despite the great strides that have been taken, most South Africans still remain plagued by disease, and persisting social disparities, including continued inequalities in access to and quality of prevention and treatment services. Other concerns having negative implications in access to healthcare include the number of people still living below the Lower Band Poverty Line, which increased from 36,4% in 2011 to 40% in 2015. Fluctuating inequality is also observed in terms of income, wealth and opportunity, while racial and gender inequalities also persist.

Development Benefits of the NHI

The 2030 Agenda positions health and well-being at the centre of sustainable development (WHO, 2016). The Agenda provides for strong political commitment to public health, arguing that socio-economic inequalities, though existing in all countries, have important implications for the health status of communities in the developing countries in particular. The lower socio-economic status could result in a higher risk of disease and death and poorer assessment of health among communities. Health systems also tend to be weaker in rural and remote areas, making rural communities the most vulnerable and disadvantaged. Poor social and living conditions characterised by inadequate access to health facilities and services, such as slums and informal settlements, also make people prone to health problems.

The World Health Organisation (2016) sees good health both as a precondition and an outcome for sustainable development. Health, together with education, housing, food and water, are also considered as part and parcel of constitutional rights that impact on the enjoyment of fundamental rights to life, equality and dignity. Mayosi and Benatar (2014) argue that a complex relationship exists between health and wealth and that this has implications for development and the well-being of people, suggesting that the life span and productivity of individuals become affected under conditions of extreme poverty for the majority in the country. The multiple determinants of health such as the social, economic, cultural and political aspects translate to availability of decent and adequate shelter, food security, and proper sanitation, and set the scene for improved health and the ability to make a living and contribute to the development of a country. A healthy and nutritious diet, adequate housing, availability of employment opportunities, and access to good quality education make it possible for people to realise their full human potential, which leads to productive and sustainable development. Tangcharoensatien et al. (2015) believe that sustainable development needs multidimensional and multisectoral policy interventions, which include paying attention to access to high-quality healthcare, employment, decent work, poverty, food insecurity and malnutrition, quality education and environmental protection or management. A healthy nation that has equality of access to quality health services characterised by health equity and protection is critical to the development of a country (WHO, 2016). This, however, requires the expansion of health coverage and having effective funding mechanisms for the health insurance system to ensure its long-term sustainability.

Funding Mechanisms of the National Health Insurance Initiative and Implications

Within the South African context, the state provides social security through tax funding. As McIntyre et al. (2009) demonstrate 40% of healthcare funding is derived from tax revenue for public sector services, whilst 85% of the population is dependent on public sector primary care services. For the proposed NHI, it is envisaged that there will be a single pool of funds coming from the general tax revenue and mandatory contributions by formal sector workers and their employers (McIntyre, 2009). The informal sector is automatically excluded due to inability to trace and tax accordingly. Government revenue is mainly raised through levying taxes on income, wealth and transactions. However, in principle, any method of government finance has to meet certain criteria including efficiency, equity, administrative ease and transparency. Hyman (2014), however, shows that these criteria are sometimes mutually exclusive. For instance, a trade-off exists between equity and efficiency, where the equitable distribution of resources may not be in line with the desired optimum taxation method. It is in the spirit of achieving these criteria that the proposed tax changes in the NHI proposals can be judged. It is also important to note that a universal healthcare system can only be based on the ability to pay principle, as opposed to the benefit principle which argues that tax is levied according to what one benefits.

Shah (2007) argues for a performance-based budgeting system in which budget allocations are tied to performance metrics. The premise of this approach is that policy decision- making should be informed by clear, achievable objectives. The shift to a performance-based budgeting system is supported by Hager et al. (2001) and Diamond (2003) whose work demonstrate that the focus on centralised budget allocation and input controls is not enough to ensure budgetary efficiency. Thus, major policy parameters should be linked to the key performance indicators (KPIs). Diamond (2003) suggests three main objectives for a modern budgetary system, namely, ensuring control over expenditure, stabilising the economy, and achieving efficiency in service delivery.

The proposed NHI Fund and the health insurance initiative itself can only succeed to the extent that clear objectives are articulated for the policy and measurements are provided that are able to inform decision-makers on the success of the implemented policy measures (Aristovnik and Seljak, 2009; Diamond, 2003). Furthermore, it is important for policymakers to engage with the affected population and derive enough input on the constituency’s expectations, and also communicate expectations and the responsibilities that community members would be expected to bear. This function is currently being undertaken as the bill has been put in the public domain for debate. However, the success of this drive depends largely on the extent to which citizens are involved in the consultations. In addition, the government will need to formulate metrics for performance measurement clearly, and which can be used in future budget allocations. Whilst it might not be achievable to link every performance metric to the KPIs, Aristovnik and Seljak (2009) argue that designing a well-functioning performance budgeting system involves determining the vision, mission and objectives of the policy. In turn, these will determine the link between inputs and outputs (deliverables) of the proposed policy.

Direct Taxes

Income taxes comprise the largest contributor to Government revenue in South Africa. Personal income tax is the major source of income tax, followed by corporate income tax. Income taxes in South Africa are progressive and based on the ability to pay.

Personal Income Tax

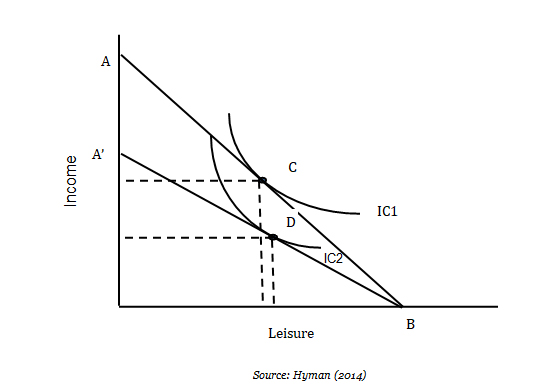

The impact of personal income taxes on welfare can be analysed using labour-leisure trade-off analysis. Levying a general income tax on the populace results in welfare losses through negative effects on efficiency, as illustrated in Figure 1. In Figure 1, the line AB shows the income-leisure trade-off facing the consumer. If the consumer chooses to work and does not allocate any time to leisure, she will earn total income at A. At B, the consumer earns zero income but allocates all her time to leisure. However, due to the convex nature of the consumer’s indifference curves, the equilibrium would occur at point C where the consumer’s indifference curve IC1 is in tangent with the budget line AB. Levying an income tax swivels the line AB to A’B and lands the consumer at a lower indifference curve IC2 and a new equilibrium at D. At point D, the consumer derives less utility from their activities than before, signifying a loss of welfare.

Figure 1 illustrates possible efficiency losses that can emanate from an increase in income taxes through their effects on the incentive to work. Due to increased income tax, employees may reduce their hours of work and increase leisure time. The disincentive to work could impact on employee productivity and ultimately lower output. In addition to losses of efficiency that may result from increases in income tax, this type of tax is closely tied to the developments in the rest of the economy. Keynesian and Neo-classical theories of economic growth relate the rate of unemployment to the growth of the economy (Solow, 1988). On the other hand, endogenous growth theories also link health to economic growth, suggesting complex interrelationships between macroeconomic variables and health (Bloom et al., 2018). The higher the growth rate of the economy, the higher the job creation and, consequently, lower unemployment can be achieved. Additional revenue needed for the NHI programme may be difficult to raise given the recent performance of the South African economy and the increases in the unemployment rate. In essence, the lower number of employed individuals in proportion to the whole population reduces the tax base. It is, therefore, imperative to pay attention to the slow rate of growth of the economy as it will inevitably result in lower income tax revenue, which may then inhibit the success of the NHI revenue mobilisation drive. The current rate of economic growth in South Africa is 1.3%, and the unemployment rate is reported at 29%. The statistics are not encouraging with regard to the NHI, as its implementation will require increased revenue collection from a shrinking tax base. This conclusion is supported by the slow pace of economic growth over the past ten years, leaving the economy vulnerable to economic shocks that may emanate from different economic sectors.

Figure 1. Effect of personal income tax on consumer work preferences

Source: Hyman (2014)

Corporate Income Tax

Corporate income tax is levied on the earnings of the business before dividends are subtracted. In Hyman (2014), corporate taxes are discriminatory as they only affect one form of business enterprise, leaving other forms such as partnerships or sole traders outside the tax bracket. In addition, not all firms are required to pay corporate tax in South Africa. In the new turnover tax regime in place, small companies with a profit of less than R335 000 will not pay any taxes. Those which earn a turnover between R750 001 and R1 000 000 will pay the highest tax, R6 650 plus 3% of the amount above R750 000 ( National Treasury, 2015). The reduction in these taxes can potentially increase investment as this is an incentive to promote small and medium enterprises. These facts underscore the notion that corporate income tax is not equitable.

Another argument raised against corporate income tax is that dividends paid to shareholders are double taxed. Hyman (2014) argues that double taxation of dividends can act as a deterrent to investors in corporate firms. A corporate tax results in a reduced return on capital for investors, leading to re-allocation of investment funds from the corporate sector to the non-corporate sector. In general, corporate taxes lead to a decrease in return in both the corporate business sector and the non-corporate business sector. The result is a disincentive to invest that can negatively influence the growth of the economy.

Indirect Taxes

The main indirect taxes used in South Africa make up the group of general taxes. These include value-added tax, excise duties and levies, transfer duty, and also import duties and levies tax. The proposal in the NHI documents is to increase general taxes to meet the revenue needs of the proposed public health insurance system. The amount targeted to be raised is equivalent to 3% of the country’s GDP. The main general taxes covered can also be categorised as consumption taxes. In general, consumption taxes are price- distorting as they alter the ultimate price paid by the consumer or the amount received by the seller.

Value Added Tax

Value-added tax (VAT) is a form of consumption tax levied on all goods and services purchased by the consumer. VAT is argued to be regressive in nature as it collects a larger proportion of income from lower-income earners compared to high-income earners. Increasing VAT, therefore, harms low-income earners. In addition, VAT is not easy to implement and ensure compliance as businesses have to register as VAT vendors. It is likely that small and medium enterprises in some cases, may not collect and pay VAT.

Excise tax

The illustration below (Figure 2) shows the distortionary effect of an excise tax. Excise taxes are levied on goods that are undesirable for consumption by society, such as tobacco.

Figure 2. Tax incidence of a unit excise tax

Source: Hyman (2014)

In Figure 2 the original consumer budget line is AB. That is if no tax is levied on tobacco products, the consumer’s equilibrium is point E, where AB intersects with indifference curve (U3). Y1 is the equilibrium expenditure on other goods and services, while AY1 is the expenditure on tobacco products. The quantity of tobacco products consumed is Q1. Consumer equilibrium is achieved at a higher indifference curve. Levying a unit excise tax on tobacco products will cause the budget line to swivel from AB to AB′. Consumer equilibrium becomes E′ where consumption of tobacco products reduces to QT, whilst expenditure on other goods and services increases to YT. AY* is the tax payable to the government. However, the consumer’s utility has decreased because equilibrium is now attained at a lower indifference curve U1 as compared to the original indifference curve U3. The consumer’s disposable income has also been reduced by tax T. Thus, to the extent that the decrease in consumption of tobacco products contributes to the health of South Africans, a unit excise tax can contribute to improvement in the health of South Africans whilst at the same time tax revenue raised can contribute to the NHI programme.

Fiscal Policy Implications of the NHI Proposal

The government of South Africa utilises fiscal policy to regulate economic activity in short to medium run. Fiscal policy involves the use of taxation, government spending and government debt to determine the level of economic activity and respond to economic shocks. For an economy in a downtrend, the stimulus could come in the form of reduced taxes or increased government expenditure. It should be noted, however, that the effect of adjustments in taxation on the economy depends on the elasticity of demand and supply. Lowering taxes increases the consumer’s disposable income and can result in increased consumption, which in turn increases aggregate demand.

Given that the government is planning to increase general taxes, the effect on economic activity could be negative, as an increase in taxes results in lower consumption which, in turn, reduces aggregate demand. Thus, a contractionary fiscal policy through an increase in taxation could be detrimental to the economic growth objective of the government as the economy is already suffering from low economic growth. While an increase in taxes, assuming constant expenditure would result in the reduction of the budget deficit, it is not clear whether the increase in tax revenue would be enough to cater for the NHI programme. Given the lack of clarity around the expected total cost of the NHI (Naidoo, 2012; Sekhejane, 2013), the budget deficit may increase. An increase in the budget deficit is undesirable for several reasons. The current debt level of the central government is already higher than expected; the recent credit rating downgrades also mean that acquiring debt is now expensive for the country; and the slow rate of economic growth could imply that debt repayment will be difficult as revenue grows at slower rate than the national debt or the interest rates thereof.

The Financing Framework for the Public Health System

In the current national public finance framework, the minister is required to table the national budget in parliament before the beginning of a fiscal year. Provincial members of the executive council (MECs) are expected to table the provincial budgets two weeks after the national budget has been announced (Public Finance Management Amendment Act 29, 1999). Important aspects of both the national and provincial budgets are the total revenue, current and capital expenditures, and debt and interest payment schedules. The proposed NHI framework, however, proposes the allocation of funds to an independent parastatal that will distribute the funds to provinces, as opposed to following the present system in which funds are distributed to the provinces directly from the National Treasury.

The Feasibility of the Proposed Procurement System

The NHI proposes a procurement system in which the NHI fund will be created to distribute funds from the national level to different provinces, local government and the private sector. This proposal hinges on a well-functioning governance system in which public goods can be delivered efficiently. Any form of government financing should be evaluated according to its impact on equity, efficiency and administrative efficiency. In practice, however, there are constraints on efficient service and goods delivery by governments. Bureaucracy, corruption, rent-seeking behaviour, and information asymmetries are some of the problems associated with government provision of public goods. Although the South African government believes that the tax system is efficient and fair (National Treasury, 2015), it is also acknowledged that corruption and waste remain challenges in the system. Bloom et al. (2018) argue that for any procurement system to be transparent, there needs to be accountability and responsibility. In addition, value for money should be preserved, and the procurement system should have clear procedures that allow for a comprehensive audit.

Corruption Watch South Africa segment the types of corruption into the abuse of power, bribery, employment corruption, and procurement corruption. In their 2018 annual report, procurement corruption’s share is 21% of total corruption in the country. This share is high and could be a major determinant of the success of the NHI programme if the attitude towards corruption is not changed. Furthermore, Corruption Watch South Africa’s reports corruption by the institution and shows that local government, national government and provincial government contribute 23%, 27% and 35% respectively to the total corruption reports compiled. These numbers are significant, given that NHI funds are expected to be channelled through these levels of government to reach the ultimate benefactors.

In addition, the overall revenue received will depend on the ability to reduce the incidence of tax evasion and tax avoidance. Tax evasion refers to illegally withholding taxes that are due, whilst tax avoidance refers, inter alia, to a change in behaviour rising from the desire not to pay taxes. Tanzi (2000) argues that the administration of taxes is poor in developing countries, and this may lead to less revenue being collected. This is noted in the National Treasury (2015) and Benn (2013), and the South African government is set to address the problems of base erosion and profit shifting, which were identified as possible impediments to revenue collection. Thus, whether the centralised system of procurement will work or not depends largely on the efficiency of the governance system in overcoming impediments such as corruption and bureaucracy.

Conclusion

This paper has reviewed the feasibility of the changes in tax structure proposed in the NHI documents by analysing the tax incidence of both income taxes and consumption-based taxes. Increasing both taxes could result in loss of welfare to society at large as labour is discouraged from working and the poor are further disadvantaged through increases in taxes such as VAT. Furthermore, distortions may arise within the fiscal policy framework, and instability could result from the tax increases. The paper also demonstrates the challenges arising from the centralising procurement of health services due to high levels of poor governance and service delivery inefficiencies. In conclusion, successful implementation of the NHI requires improved governance, a clear understanding of its policy implications, and continuous monitoring of its implementation to prevent any financial leakages and ensure efficiency in service delivery.

References

Aristovnik A and Seljak J (2009), Performance budgeting: selected international experiences and some lessons for Slovenia. University of Ljubljana. Slovenia.

Benn DJ (2013), Tax avoidance in South Africa: an analysis of general anti-avoidance rules in terms of the Income Tax Act 58 of 1962, as amended (Doctoral dissertation, University of Cape Town).

Bloom DE, Khoury A and Subbaraman R (2018), The promise and peril of universal health care. Science, 361(6404), p.9644.

Bloom DE, Kuhn M and Prettner K (2018), Health and economic growth. Discussion Papers, (IZA DP No. 11939). Bonn, Germany.

Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation (2019), 25 Year Review Report 1994-2019. Pretorie: Republic of South Africa.

Diamond M J (2003), Performance budgeting: managing the reform process: International Monetary Fund.

Hager G, Hobson A and Wilson G (2001), Performance-Based Budgeting: Concepts and Examples (No. 302). Legislative Research Commission, Committee for Pram Review and Investigations.

Harris B, Goudge J, Ataguba JE, McIntyre D, Nxumalo N, Jikwana S and Chersich M (2011), Inequities in access to health care in South Africa. Journal of public health policy, 32(1): 102-123.

Hyman D N (2014), Public finance: A contemporary application of theory to policy: Cengage Learning.

Mayosi BM and Benatar SR (2014), Health and health care in South Africa—20 years after Mandela. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(14):1344-1353.

McIntyre D, Goudge J, Harris B, Nxumalo N and Nkosi M (2009), Prerequisites for national health insurance in South Africa: results of a national household survey. South African Medical Journal, 99(10): 725-729.

McLeod H (2008), National Health Insurance in South Africa. South African Pharmaceutical Journal, 75(5): 8-11.

Naidoo S (2012), The South African national health insurance: A revolution in health-care delivery!. Journal of Public Health, 34(1):149-150.

National Treasury (2015), Government expenditure and Tax policy. Pretoria: National Treasury of the Republic of South Africa.

Republic of South Africa (1996), The Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act 108 of 1996: Government Printers, Pretoria.

Republic of South Africa (1999), Public Finance Management Amendment Act, No. 29. Pretoria, Government Printer.

Sekhejane P (2013), South African National Health Insurance (NHI) Policy: Prospects and Challenges for its Efficient Implementation. AISA Policybrief, number 102-December 2013:1-5.

Shah A (2007), Budgeting and budgetary institutions: The World Bank.

Solow RM (1988), Growth theory and after. The American Economic Review, 78(3): 307-317.

Tangcharoensathien V, Mills A and Palu T (2015), Accelerating health equity: the key role of universal health coverage in the Sustainable Development Goals. BMC medicine, 13(1):101.

Tanzi MV (2000), Tax policy for emerging markets-developing countries: International Monetary Fund.

World Health Organization (2016), World health statistics 2016: monitoring health for the SDGs sustainable development goals. World Health Organization.

World Health Organization (2018), Delivering quality health services: a global imperative for universal health coverage. World Health Organization, World Bank and OECD.

World Health Organization (2019), Primary health care on the road to universal health coverage: 2019 monitoring report: executive summary (No. WHO/HIS/HGF/19.1). World Health Organization.